Cause of lupus, possible cure identified, researchers say in new study

Doctors treating lupus have long been unable to determine the autoimmune disease’s cause.

On the other hand, molecular abnormalities in patients’ blood were the basis for a lupus aetiology discovered this week in a study published. Certain cells are overproduced in lupus, attacking the body’s tissues and organs. Thousands of Americans are afflicted by the incurable sickness.

To help control lupus, researchers are attempting to achieve a balance with the cells. Immunosuppressants are now used in treatment to lessen pain and inflammation, but researchers have shown that these medications frequently don’t properly treat the disease and that their side effects make it harder for the body to fight against infections.

“Every lupus treatment up until this point is a blunt instrument. It’s broad immunosuppression, according to a statement from Dr. Jaehyuk Choi, an associate professor of dermatology and dermatologist at Northwestern Medicine and co-author of the study. “We have discovered a potential cure that will not have the side effects of current therapies by determining the cause of this disease.”

Researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, as well as Choi’s colleagues at Northwestern, participated in the study that was published this week in the journal Nature. Blood samples from 19 people with systemic lupus erythematosus—the most common kind of the autoimmune disease—and 19 patients without it were compared.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than 200,000 Americans suffer from lupus, but the charity Lupus Foundation of America believes the actual figure is closer to 1.5 million. People of colour and women make up the majority of lupus patients. According to the CDC, Black women are more likely than other groups to get the disease, suffer from more severe forms of it, and die from it at a higher rate. Although the majority of lupus patients survive, the Lupus Foundation estimates that 10 to 15% of patients experience premature death from the disease’s consequences.

Prior to the study’s publication this week, lupus’s aetiology was unknown. According to the National Institutes of Health, experts postulated that immunological and inflammatory impacts, chemicals or viral infections in the environment, or heredity could all be contributing factors.

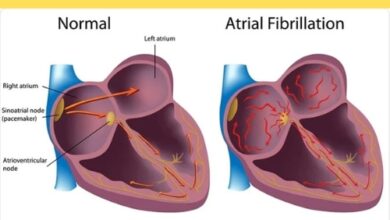

Extreme exhaustion, discomfort or swelling in the muscles and joints, skin rashes (such as a butterfly-shaped rash on the cheekbones or nose), fever, and hair loss are common symptoms of lupus. It results in many health issues, such as memory loss, seizures, and kidney failure. According to the NIH, it damages the brain and central nervous system and induces cardiac issues.

Despite being preliminary and based on a tiny sample of blood tests, the findings by Northwestern and Brigham and Women’s researchers may provide some hope.

Researchers have discovered a novel lupus cause. The study participants exhibited a chemical dysregulation that regulated the immune system’s T cells’ response to infection. T cells are a subset of white blood cells.

According to Choi’s email, individuals with lupus exhibited elevated levels of interferon, a protein that aids in fighting infection, and decreased levels of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) proteins, which control the body’s reaction to infection. As a result, the body was attacked by an excess of cells that promote disease. Researchers have found that substituting inactive AHR molecules with active ones may help heal wounds rather than causing more damage.

According to a news release, the researchers activated the AHR in blood samples from lupus patients, which seemed to rewire lupus-causing cells to aid in healing.

According to Choi, the study has the potential to lead to novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of lupus. To better protect patients from the condition, the objective is to target the cells that cause it.