No, Fake Meat Wasn’t Found to Cause Heart Disease, as Some Headlines Suggest

A recent study found that eating ultraprocessed plant-based foods was linked to heart attack and stroke risk. But the devil is in the details

The use of plant-based imitation meat, like vegetarian sausages and textured vegetable protein, has been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and death, according to recent headlines criticizing these foods as harmful. However, a further examination of the research supporting these assertions points to a more complex picture.

The article that sparked the headlines claims that the true offenders are “plant-based” ultraprocessed foods in general, not meat replacements specifically. However, there’s a crucial disclaimer: “Plant-based” diets might include items you might not anticipate, such soda, frozen pizza, and biscuits dipped in chocolate. An elevated risk of cardiovascular-related illnesses and mortality was associated with ultraprocessed plant-based diets, according to a study published earlier this month in the Lancet Regional Health–Europe.

But the amount of plant-based meat consumed by research participants was rather small, and the study was not intended to identify the precise items that were most strongly associated with unfavorable health outcomes. However, detractors argue that the ambiguous interpretations highlight how intricate nutrition research can be, as scientists’ notions of food do not always align with what the general public may understand to be a plant-based diet.

When food goes through an industrial transformation that drastically changes the original constituents, it’s referred to as ultraprocessed food. Before these items get up on your plate, they travel a great distance. Basic pantry items like store-bought cookies and instant noodles usually go through multiple processing steps that reveal the fundamental structure of their base materials. After that, they are put back together with an emphasis on flavor and convenience, frequently using a combination of additives to improve appearance and shelf life. The general rule is to “think of a food you wouldn’t be able to prepare in your own kitchen,” according to Evangeline Mantzioris, a dietician and researcher at the University of South Australia who was not involved in the study. This could be due to the food’s chemical composition or the industrial machinery required to prepare it.

A framework known as the NOVA classification system is used as a standard in nutrition research, notably in this much discussed publication, to group foods along a spectrum from unprocessed to ultraprocessed depending on the degree of change from their natural condition. The majority of foods fit into intuitive categories. While morning cereals and canned soups are deemed ultraprocessed, beans and broccoli are not. Some, though, might not be immediately apparent. For instance, spirits like vodka were deemed ultraprocessed in the recent Lancet Regional Health–Europe study, yet beer and wine were listed as examples of non-ultraprocessed beverages.

This concept is used in food research because, according to senior author Fernanda Rauber, a nutritional epidemiologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, preparing food may fundamentally alter how it interacts with the body to effect health. According to her, food’s health benefits come from more than “the sum of its nutrient functions.” “Food combinations, preparation methods, and meal consumption all significantly influence how foods affect one’s health.”

In the study, Rauber and her associates connected hospital and mortality statistics pertaining to cardiovascular diseases with individuals’ daily dietary intake. The researchers used information from over 100,000 adult U.K. volunteers in BioBank, a sizable database that monitors the health, way of life, and genetic makeup of individuals between the ages of 40 and 69.

According to Gunter Kuhnle, a nutritional epidemiologist at the University of Reading in England who was not involved in the study, the plant-based group in the study was kind of a catch-all. Upon initially reading the paper’s title, Kuhnle believed it solely discussed plant-based substitutes for animal-derived goods, such as plant-based milk, plant-based drinks, and plant-based meat alternatives. “It became pretty obvious that it was not that after reading the paper,” he says. Additionally, the press release underlined that interpretation, saying in the opening paragraph that goods like plant-based sausages, nuggets, and burgers that were “intended to replace animal-based foods” were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

However, Kuhnle adds that there is more to the story: ultraprocessed items that were less obviously “plant-based,” such as bread, cakes, sugar-filled drinks, potato chips, and ketchup, were compared to meat substitutes. These foods are not typically associated with a plant-based diet. He claims that such a broad classification was “not wrong.” “It was just simple to misinterpret.”

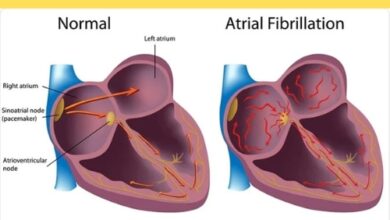

According to the study, people who consumed more ultraprocessed foods had a higher risk of developing heart disease or passing away from it. These findings “weren’t really that surprising,” according to Kuhnle, considering that the study included “plant-based” foods like sugary drinks and foods that many dietary guidelines advise against consuming in excess.

For every 10% increase in consumption of plant-sourced ultraprocessed foods (which included cookies, chocolate bars, tofu, and tempeh), as a percentage of total energy intake, the risk of cardiovascular disease increased by 5%, and the chance of dying from the disease increased by 12%. The opposite was also true: the risk of heart disease decreased by 7% and the death rate decreased by 13% for every 10% increase in the consumption of non-ultraprocessed but still plant-based meals like pasta, beans, and potatoes.

The issue is that because the foods are analyzed collectively, this kind of analysis cannot determine whether one particular item is better or worse than another. Furthermore, the so-called plant-derived, ultraprocessed foods, such as packaged breads, made up only 10 percent of the total calories consumed by individuals, with tofu, tempeh, and textured vegetable protein products making up only 0.2 percent. In reaction to how the study has been depicted in some media coverage, Rauber states, “We cannot draw specific conclusions related to this particular type of food.”

Still, the results contribute to an increasing amount of data that shows ultraprocessed meals are associated with harmful health effects. Eating more ultraprocessed food was linked to a number of health hazards, including cardiovascular illnesses, according to a new analysis of several studies that combined data from nearly 10 million individuals. It’s less certain how imitation meat products may affect your health. Though it did not look at the long-term health impacts of such eating patterns, a recent study found that plant-based eaters, including vegetarians and vegans, favored bad plant-based foods over better ones and consumed more ultraprocessed foods than meat eaters. However, ultraprocessed meats themselves, including salami and sausages, have been connected to increased mortality from all causes, including colon cancer.

It’s still unknown exactly how ultraprocessed foods could be harmful to one’s health. While some studies blame the high saturation levels of fat, sugar, and salt in these foods, other study raises the possibility that the process of processing food—which involves transforming its natural structures into something new—may have unidentified health effects on the body. Acrolein, one of the contaminants that may arise from frying, baking, or fermenting ultraprocessed foods, and other chemical additives like the popular flavor enhancer monosodium glutamate (MSG) may also have an impact on appetite and health. Acrolein has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in the past.

Rauber warns that cause and effect could not be separated in the study. Because people’s eating habits are messy and rarely follow a regular regimen over an extended period of time, it is difficult to construct research that can conclusively determine if a given diet causes a disease. However, Mantzioris notes that “there are huge amounts of evidence… to tell us that ultraprocessed foods are probably not doing the best thing for our health” due to the abundance of observational studies that are currently available. Rauber’s study took into consideration additional factors, including the potential impact of ethnicity, physical activity, and family history on a person’s risk of heart disease.

According to Kuhnle, eating ultraprocessed food isn’t always a “good” or “bad” decision and should be considered in the larger context of a person’s diet, bearing in mind that the effects of ultraprocessed food on health take time to manifest.